рефераты конспекты курсовые дипломные лекции шпоры

- Раздел Лингвистика

- /

- The Nature and Role of Information

Реферат Курсовая Конспект

The Nature and Role of Information

The Nature and Role of Information - раздел Лингвистика, Аннотирование и реферирование английской научно-технической литературы Text 32 Social Welfare State And Voluntary ...

Text 32

Social welfare

State and voluntary services

In Britain the State is now responsible, through either central or local government, for a range of services covering family allowances, social insurance, help for war victims, financial assistance when required, health and welfare services for mothers and young children, the sick, mentally disordered, elderly and handicapped and for families in difficulties of various kinds, and the care of children lacking a normal home life (all described in this chapter); and for education (see Chapter 6), housing (see Chapter 7) and employment services (see Chapter 16). Public authorities in the United Kingdom are spending about 5,230 million a year on this range of services; that is, over 97 a year per head of the population.

Voluntary organisations, especially the Churches, were the pioneers of nearly all the social services. They provided schools, hospitals, clinics, dispensaries, and social and recreational clubs before these were provided by the State. They made themselves responsible for the welfare of the very young and the very old, the homeless and the handicapped. Gradually the State accepted the primary responsibility for the major services, supplementing the voluntary services and developing a comprehensive structure that ensured a minimum standard of living and wellbeing for all citizens.

State and voluntary social services are now complementary and co-operative. The State often works through voluntary agencies specially adapted to serve particular needs and ensures that necessary standards are maintained. The officers of central and local government, in carrying out their duties, co-operate with the workers of many voluntary social service societies, while the residential provision made by the State and by local authorities for the care of the chronic sick and the aged is supplemented by voluntary homes of various types for the care of the sick and elderly, most of whom receive State pensions or benefits.

The Charity Commission, a government department, gives free advice to trustees of charities, making schemes to modify their trusts and purposes when necessary; it maintains a Central Register of Charities in which information about all the charities in England and Wales is being gathered together; and it works to promote co-operation between charities and State services.

Voluntary Organisations

The number of voluntary charitable societies and institutions in Britain runs into thousands; they range from national organisations to small individual local groups. Most organisations, however, are members of larger associations or are represented on local or national co-ordinating councils or committees. Some are chiefly concerned with giving personal service, others in the formation of public opinion and exchange of information.

Organisations concerned with personal and family problems and misfortunes include the voluntary family casework agencies, of which the Family Welfare Association, working mainly in London, is the best known; marriage guidance centres affiliated to the National Marriage Guidance Council; and the Family Service Units.

Voluntary service to the sick and disabled in general is given by the British Red Cross, the St. John Ambulance Brigade and the St. Andrew's Ambulance Association, but a number of societies exist to help sufferers from particular disabilities, such as the Royal National Institute for the Blind, the Royal National Institute for the Deaf, the National Association for Mental Health, the constituent members of the Central Council for the Disabled and their Scottish equivalents.

Bodies working on a national scale whose work is specifically religious in inspiration include the Salvation Army, the Church Army, Toe H, the Committee on Social Service of the Church of Scotland, the Church of England Children's Society, the Church of England Council for Social Work, the Young Men's Christian Association, the Young Women's Christian Association, the Society of Friends, the Crusade of Rescue, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, the Catholic Marriage Advisory Council and the Jewish Board of Guardians.

A wide range of voluntary personal service is given by the Women's Voluntary Service, which 'lends a hand' in every kind of practical difficulty, brings 'meals on wheels' to housebound invalids and old people, minds children, and visits the sick in hospital, as well as doing relief work in emergencies.

A central link between different voluntary organisations and official bodies concerned with social welfare is provided in England and Wales by the National Council of Social Service, which brings together most of the principal voluntary agencies for consultation and joint action, either as a whole or in groups of those concerned with particular aspects, such as youth work or old people's welfare. There are also the Scottish Council of Social Service and the Northern Ireland Council of Social Service, which perform similar coordinating functions in the voluntary sphere. It was the National Council of Social Service, which set up the Citizens' Advice Bureaux, of which there are now about 430 in Great Britain. The primary role of the bureaux is to give explanation and advice to the citizen who is in doubt about his rights or who does not know about the State or voluntary service which could help him.

Social Workers

While the voluntary worker giving full-time or part-time service has done pioneer work in many of Britain's social services and continues to play an essential part, social services of all kinds increasingly depend for their operation chiefly on the professional social worker, that is, the full-time salaried worker trained in the principles and technique of social work. Training for many forms of social work consists of a basic university degree, diploma or certificate course in social science followed by a university course in applied social studies or specialised training for a particular service. The latter is sometimes organised by the profession concerned. Under the Health Visiting and Social Work (Training) Act 1962 a Council for Training in Social Work was set up to promote the training, in the first instance, of workers in the local authority health and welfare services and similar services run by voluntary bodies. Full-time courses lasting two years, now being provided by eleven colleges of further education, lead to the Council's Certificate in Social Work. More courses are being arranged, including two starting in October 1965 in Scotland.

Voluntary organisations were the pioneers in the employment and training of social workers, but government departments and local authorities now employ a considerable number of trained social workers, for example, in child care, youth work, medical-social work, psychiatric social work, and the probation service.

Immigration and Welfare

In recent years many people from Commonwealth countries in Asia, Africa and the West Indies have entered Britain to take up employment, some with their families but many alone, their families coming later. Often they concentrate in large industrial areas where they add to the demand for housing and increase the pressures on educational facilities and other social services.

In 1965, because the Government was not satisfied with progress in integrating Commonwealth immigrants into the community, the Prime Minister appointed one of the Parliamentary Under-Secretaries of State in the Department of Economic Affairs to be personally responsible for coordinating government action and promoting the efforts of local authorities and voluntary bodies to deal with the various social and economic problems.

The Commonwealth Immigrants Advisory Council, which was set up in 1962, has published three reports on these problems. On its recommendation a non-official National Committee was set up in 1964. The Government intends to replace these two organisations by a new National Committee for Commonwealth Immigrants which will promote integration efforts on a national basis.

The Race Relations Bill 1965, of which the main object is the introduction of legal sanctions against discriminatory behaviour, provides for local conciliation committees to inquire into complaints of racial discrimination in places of public resort and a Race Relations Board to look into cases where conciliation is not achieved. If necessary, the Attorney-General would take proceedings in the civil courts.

Social security

National Insurance, Industrial Injuries Insurance, ramily Allowances and National Assistance together with (in a special category) War Pensions, constitute a comprehensive system of social security in the United Kingdom which ensures that in no circumstances need any one fall below a certain minimum standard of living.

The Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance administers the first three of these services in Great Britain; in Northern Ireland they are administered by the Ministry of Health and Social Services. National Assistance is administered by the National Assistance Board in Great Britain, and in Northern Ireland by the National Assistance Board for Northern Ireland. Pensions and welfare services for war pensioners and their dependants are the responsibility of the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance throughout the United Kingdom. Appeals relating to claims for insurance benefits, family allowances or war pensions, or to applications for assistance, are not decided by the Ministries or the Boards but by independent authorities appointed under relevant legislation.

Although the development of public provision for social security in Britain can be traced back for several centuries (the Poor Relief Act of 1601 maybe regarded as specially important in England and Wales), the modern system of comprehensive provision is a creation of the twentieth century. Non-contributory old age pensions were introduced in 1908, and the first contributory pensions for old people, widows and orphans in 1926. A contributory National Health Insurance Scheme was begun in 1912, and in the same year a scheme of unemployment insurance was introduced which in 1920 was extended to cover the great majority of employees. By the beginning of the second world war social security provision in Britain was among the best in the world, but lacked co-ordination by the very fact of its piecemeal development, and not everyone came within its scope. In the immediate post-war years a series of Acts introduced the present comprehensive system, which became fully operative on 5th July, 1948. Adjustments have been made by a number of subsequent Acts. Statutory provision for the war disabled goes back to the end of the sixteenth century, but the main lines of the present war pension provisions were laid down during the first world war.

Family allowances and national insurance benefits or allowances, other than maternity, unemployment or sickness benefit, are included in the taxable income on which income tax is assessed. On the other hand, various income tax reliefs and exemptions are allowed on account of age or liability for the support of dependants. War disablement pensions are not taxable.

Reciprocity

The national insurance, industrial injuries and family allowances schemes of Great Britain and those of Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man operate as a single system. Reciprocal agreements on industrial injuries, family allowances and all, or most, national insurance benefits are in operation with Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the German Federal Republic, Guernsey, Jersey, Norway and Yugoslavia. Agreements with France, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey cover industrial injuries and most national insurance benefits. With Australia, Canada and New Zealand there are agreements on family allowances and some, or most, national insurance benefits. There is an agreement with Cyprus on national insurance, and one with the Irish Republic which covers some national insurance benefits; it also contains some industrial injuries provisions relating to seafarers. Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man, as well as Great Britain, are party to most of the agreements with other countries.

Family allowances

Family allowances are provided in Great Britain under the Family Allowances Act 1945, and in Northern Ireland under the Family Allowances Act (Northern Ireland) 1945. Nearly 6 million allowances are being paid in Great Britain to about 3 million families with two or more children and over a quarter of a million in Northern Ireland to 118,000 families. An allowance is paid for each child other than the first child below the age limits. The age limits are 15 years for children who leave school at that age, 16 years for certain incapacitated children, and 19 for children who remain at school or are apprentices. The rate of the allowance is 8s. a week for the second child below the age limits and los. a week for the third and each subsequent child.

Family allowances are paid from the Exchequer and their object is to benefit the family as a whole; they belong to the mother, but may be paid either to the mother or to the father. There is no insurance qualification for title to the allowances, but there are certain residence conditions.

National Insurance

The National Insurance Acts 1946-64 apply, in general, to everyone over minimum school-leaving age (15 years) living in Great Britain. There are similar schemes in Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man.

The National Insurance scheme provides benefits in specified contingencies to insured persons who have paid the required contributions. The benefits are paid for partly by insured persons' contributions, partly by contributions of employers in respect of their employees, and partly by a contribution made by the Exchequer out of general taxation. The rates of contributions (except for retirement pensions) and benefits are standard amounts varying only with the sex and insurance class of the insured person (with lower rates for those under 18). For retirement, graduated contributions and pensions were introduced in 1961; the scheme applies to all adult employed persons earning over ^9 a week and not 'contracted out' of it and provides for them to earn additions to flat-rate retirement pension (but not to any other benefit) in return for graduated contributions, related to earnings between ^9 and ^18 a week and normally paid in addition to the flat-rate contribution. Employees whose job provides them with an occupational pension, at least equivalent to the maximum State graduated pension, may be 'contracted out' of the scheme. About 4^ million employees are contracted out in Great Britain and over 39,000 in Northern Ireland.

Contributions

All three classes pay flat-rate contributions. Table 7 shows the main weekly rates of these contributions (including the National Health Service contribution, which for convenience is paid with it though the two services are separately administered). The table also shows the range of graduated contributions which are payable by employed persons aged 18 or over (unless they have been 'contracted out') who earn more than ^9 a week, at the rate of approximately 4^ per cent of that part of their weekly pay between ^9 and j^iS. The employer pays the same amount.

Flat rate contributions are normally paid on a single contribution card by national insurance stamps bought from a post office. It is the employer's responsibility in the first place to see that the class i contributions are paid, but he can deduct the employees' share from their wages. Graduated contributions are collected through the same machinery as is used to collect Pay As You Earn (deduction at source) income tax. The self-employed and non-employed must stamp their own cards. Contributions are usually credited for weeks of unemployment, sickness or injury, or if widow's benefit is being paid.

Contributors

Contributors under the National Insurance scheme are divided into three classes:

Class i. Employed persons. Those who work for an employer under a contract of service or are paid apprentices - over 23 million. This class falls into two groups: those who are, and those who are not, participating in the graduated part of the scheme.

Class 2. Self-employed persons. Those in business on their own account and others who are working for gain but do not work under the control of an employer - nearly i^ million.

Class 3. Non-employed persons. All persons insured who are not in class 1 or 2 - over a quarter of a million.

This general classification is subject to certain modifications, made by regulations, to meet special circumstances. Married women engaged only in their own household duties are, in general, provided for by their husbands' insurance and need not pay contributions. They can choose to pay contributions provided they were insured persons when they married. (Those who were already married when the scheme began to operate on 5th July, 1948, cannot be insured in their own right unless they were then insured under the old scheme and continued to pay contributions as non-employed persons, or unless they have since taken up paid work.) Employed married women may choose whether to pay separate contributions themselves or to rely on the cover provided by their husbands' contributions, which make them eligible for maternity grant, retirement pension at lower rate, widow's benefit and death grant, but they must pay graduated contributions if they are employed in a participating employment and their earnings are over 3^9 a week. Students receiving full-time education and unpaid apprentices need not pay contributions. Up to the age of 18, contributions are credited to them. Over that age they may, if they wish, pay as non-employed persons (class 3) and thus safeguard their title to widow's benefit and to retirement pension at full rate. Self-employed and non-employed persons whose income is not more than £260 a year can apply to be excepted from liability to pay contributions. They too may pay as non-employed persons to safeguard entitlement to pension.

An insured person ceases to be liable for national insurance contributions at the age of 70 for men, 65 for women, or when he retires, or is deemed to have retired, from regular employment after reaching minimum pension age (65 for men, 60 for women), whichever is the earlier. If such a person does any work as an employed person thereafter, he must pay an industrial injuries contribution; the employer still has to pay his full share of the flat-rate contribution.

Benefits

The scheme provides payments to contributors in case of unemployment (if normally working for an employer), sickness (if normally working for an employer or self-employed), and confinement and the weeks immediately before and after (for women normally working for an employer or self-employed and paying national insurance contributions at the full rate). Retirement pensions are paid to people who have reached 65 (60 for women) and who, if under 70 (65 for women), have retired from regular work; widows receive benefit in the first 13 weeks after bereavement and subsequently while they have young children or if they have reached the age of 50 when widowed or when their children have grown up; and there are two kinds of allowance in respect of orphan children where a widow's pension is not payable. The scheme also provides lump-sum cash grants for two expensive contingencies - the birth of a child and a death (though not for the death of someone already over minimum pension age when the scheme started).

For most of the benefits there are two contribution conditions. First, before benefit can be paid at all, a minimum number of contributions must actually have been paid since entry into insurance; secondly, the full rate of benefit cannot be paid unless a specified number of contributions have been paid or credited over a specified period. There are special rules to help a widow who does not become entitled to a widow's pension at widowhood or when her children have grown up, to qualify for sickness or unemployment benefit in the period before she can have established or re-established herself in insurance through her own contributions; there are also provisions to help divorced women who were not paying contributions during their marriage.

text 33

The nature and role of information

1. Introduction

Think of a place to which you have never been or a person to whom you have never been introduced. Think of some food or drink which you have never tested or a film which yon have not yet seen. You may be thinking of New York or Glasgow, the Prime Minister or the principal of the college you attend, malt whisky or bird's nest soup. Whatever you are thinking of, it must be something of which you, yourself, have absolutely no first-hand personal experience.

How is this possible? The answer, of course, is that you have been told about, or have read about, these things (and where there are gaps in your knowledge you use your imagination). You have been on the receiving end of the communication process, forming your view of the world partly on the basis of second-hand information. For no one relies exclusively on personal experience and our minds are full of ideas that do not depend for their existence on our own sensory experience.

2. Sources of information

We receive information about things from a very wide range of sources. We may read of a place in a travel brochure or learn about it from looking at a friend's holiday snaps. We may form an impression of what sort of person a professional footballer is by reading an interview in a national newspaper. Our impression of malt whisky may depend entirely on the advertisements that we see for it in glossy magazines.

Of course, our own personal experience is also a vital source of information. But we can often manage surprisingly well without it.

If you were to summarise all the sources of information which contribute to this process of idea and image formation you would probably finish up with a list something like this:

• Things you know from your own personal experience.

• Things you have read in newspapers, magazines, leaflets and books.

• Things you have seen and heard on television and radio.

• Things told to you in a formal setting, such as a college lecture.

• Things told to you in an informal setting, such as a friendly chat.

• Things you overhear - in a bus queue, for example.

• Things you see - in a shop window, for example.

All the above represent different forms of communication. Amongst all that communication there will be many examples of publicity.

3. Direct publicity and indirect publicity

A great deal of publicity emanates from an organisation in order to influence people's opinions and actions in favour of that organisation. Advertisements, direct-mail letters and speeches are examples. This is known as direct publicity and is sometimes also called promotion.

We can learn a lot about an organisation, a business for example, from the direct, publicity it puts out. We can also learn a great deal from statements made about that organisation by other people. Documentaries on television, newspaper articles, competitors and consumers can all have something to say. This is publicity of an indirect sort - it does not come to us directly from the organisation.

Case Study

Bergerac and the Island of Jersey

Sometimes indirect publicity is an accidental by-product of a piece of work which was designed to serve quite a different purpose. The television detective series Bergerac was produced to provide thrilling entertainment but in doing so it gave a great deal of publicity to Jersey, the Channel Island in which the series was set. As a consequence of this publicity visitors to Jersey increased considerably, although the programme was not designed to boost local tourism. Paradoxically, some of the residents of Jersey objected to the attention which Bergerac brought to the island. They thought that it created the image of Jersey as a place with an unusually high, and violent, crime-rate.

How many people who have never visited Jersey have an image of it based almost entirely on watching the series Bergerac? And what sort of image would they have?

In common with most holiday destinations, Jersey does have a Tourist Office whose task it is to promote Jersey in the most positive way. There is nothing accidental about the television commercials, which expound the natural and beautiful Jersey coastline. Neither is there anything accidental about the brochures describing holidays in Jersey, which you can pick up in any good high-street travel agent. These are examples of planned and deliberate publicity using paid-for means of communication to enhance the image and performance of any organisation, product, etc. Jersey has its professional image-makers whose job it is to attract visitors (and business) to the island.

Image-making

In fact, every product of every sort, a holiday, a car, an insurance policy, a tube of toothpaste or an ice-cream, has an image, and every product has its image-makers.

Now imagine that you are one of those image-makers. You are probably either working for a business organisation or acting as one of its agents. Actually, you could be working for a political party, a charity, a religious organisation, the police force, local government or a branch of the armed services.

Your job is to use your communication skills to promote the interests of your employer in a positive way. Those interests may range from increasing sales to winning elections: from raising funds to attracting new recruits: from saving the church tower to fighting drug addiction.

|

* Advertising is shown here as just one example of a promotional activity

Fig.1.1. The relationship between promotion, publicity and advertising

Whatever those interests are they will be undermined if your employer has a poor image and strengthened if your employer has a good image. It is your job to use a range of promotional techniques to enhance that image and support your employer's objectives and interests. It is also your job to be aware of all the indirect publicity that your employer may attract and, where it is unhelpful to your employer's purposes, to counter it.

It is almost certainly too big a task for just one person. A number of people with a wide range of promotional skills between them will have to work together to achieve the employer's objectives. Apart from promotional skills there is also a need for research, analysis and planning. That is what this book is about.

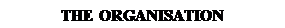

Figure 1.1 shows some of I the above ideas in relationship to each other. In the large outer circle we have all the forms of publicity to which an organisation or its products might be exposed. Some of that publicity, as we have seen, arises indirectly and is outside the control of the organisation and some of it is direct and within the organisation's control. The Jersey Tourist Board had no control over the scripts for Bergerac but it certainly controls its own television advertisements.

In the middle circle we have those aspects of publicity which we can call promotion - all the communication which an organisation does on its own behalf to improve its image and to improve its chances of achieving its objectives. Promotion includes advertising, sponsorship, direct mail, personal selling, public relations, conferences, exhibitions, etc.

In the smallest circle we have just one example of a promotional activity - advertising. We could put public relations, direct mail or any of the other items into this circle. As we go through the book the two larger circles remain unchanged - there is always publicity in its widest sense and promotion as a particular kind of publicity in a narrower sense. It is the content of the inner circle that changes as we discuss different types of promotional activity.

text 34

What is publicity and promotion?

Introduction

Any business decision is developed within the context of the organisation's environment. This will be discussed more fully in chapter 3. Here we are concerned with a particular aspect of the environment which we will call the publicity surround. Any organisation is surrounded by publicity which pervades both its internal and its external environments. As we have noted, some of the publicity is direct in the sense that it originates from the organisation (we will later define this as promotion). Some, however, is indirect in that its origin lies elsewhere - this is obviously not promotion as such.

This chapter looks in more detail at the terms publicity and promotion and, finally, at some brief definitions of particular types of promotion such as advertising and public relations. Note, however, that words like advertising are not always used in the same way by everybody. Remember also that the word publicity is used here to include each and every statement made about an organisation.

Different perspectives on publicity

* Publicity may be controlled or non-controlled. All managers have to accept that some things are outside their control and there are situations (such as when a company's products are under discussion in a consumer magazine such as Which?) where publicity comes into this category. Advertising, of course, is controlled publicity.

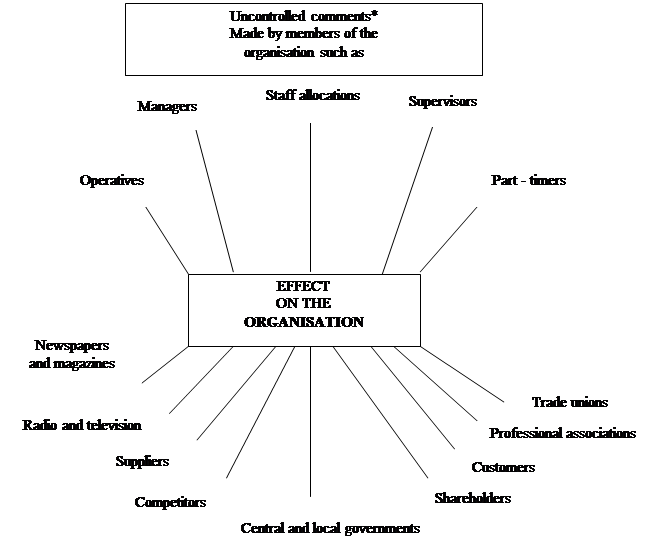

Figure 2.1 shows an organisation's controlled publicity and fig. 2.2 shows its non-controlled publicity. Figure 2.3 shows all the aspects of publicity, both controlled and non-controlled, and indicates their relationship to each other and their effect on the company's image and performance. The word publics in these figures will be explained more fully later but, for now, it can be taken to mean any audiences which the company has.

* Publicity may use any media. It may be printed - for example, in newspapers or on posters. It may be broadcast - for example, on radio and television. It may be spoken - for example, at a meeting between a salesman and a client.

* Publicity may have different degrees of permanence. Advertisements in newspapers have a degree of permanence that broadcast announcements lack. A printed advertisement may survive for months, whereas a radio commercial lasts only for a few seconds - and a piece of 'sky-writing' will last only until the wind blows it away.

* Publicity may be authorised or unauthorised. Any statement that an organisation makes on its own behalf, pays an agent to make for it, or permits a third party to make about it is authorised.

However, any person is at liberty (within the law) to make unauthorised, and often unsolicited, statements about an organisation. The difference between unauthorised and unsolicited can give rise to misunderstanding, but generally a statement is unauthorised if it is made without the consent of the organisation under discussion.

* Publicity can he solicited or unsolicited. Organisations may go out of their way to solicit publicity. Public relations offers an example of this when a firm sends out a press release announcing a new product in the hope that the product will he beneficially mentioned in the media. Another example would be when film critics are invited to preview a film prior to its release. In each case the objective is to solicit favourable comments. If, however, the comments are highly critical, as when a reviewer says that a film is not worth seeing, they can be said to be unsolicited. The film company did not encourage such things to be said.

However, the negative film review could not be said to be unauthorised. If the film producers invite a panel of film critics to preview a film they are authorising the critics to express their honest opinions about it. The producers are deliberately exposing themselves to the possibility that the critics will not like their film. In such a case the negative reviews might be said to be authorised but not solicited and may be called an 'unsought consequence' (or unsolicited consequence) of authorising the critics to preview the film in the first place.

Unauthorised or unsolicited statements are, of course, not always critical. A commentator can, and often does, make quite generous comments about an organisation without being solicited to do so.

Fig.2.1. Controlled publicity

|

Fig. 2.2. Uncontrolled publicity

*The organisation's external and internal publics or audiences are free (within legal limits) to comment on the organisation. The things said by members of one public may in turn affect the attitudes and opinions of members of other publics. The organisation may attempt to influence these comments but ultimately it has no real control.

* Publicity may be friendly, neutral or hostile. We would expect any publicity that an organisation puts out on its own behalf to be friendly. Unauthorised and unsolicited statements may, however, be hostile and any organisation (business, charitable, political, or whatever) must expect to attract some hostile comment. Comments can, of course, be simply neutral.

* Publicity can be true or untrue. Not all statements made about an organisation are true. We are not talking about differences of opinion here, as when one reviewer castigates a film which another praises but about what is, or is not, actually a matter of fact. Sometimes false statements are made in good faith by people who have simply got their facts wrong and intend no malice or deceit. There are times, however, when the publication of untrue statements may be made by people who know that what they are saying is untrue. In such cases the statements are made with the intention to deceive (and sometimes by the companies themselves).

We must not make the mistake, however, of confusing 'hostile' with 'untrue'. Not all hostile comment is dishonest or untrue - the reviewers are not lying when they say that in their opinion a film is unworthy of the cinemagoer's attention.

|

Fig.2.3. The total publicity surround

NB The organisation is constantly surrounded by publicity. Not all of this is of the organisation's own making. The effect of this publicity is felt by both the organisation and its publics.

What do we mean by promotion?

Promotion is that part of the publicity surround that can be identified clearly as having been authorised, and paid for, by the organisation itself. This definition clearly rules out unauthorised, unsolicited and hostile publicity. Sadly, it does not rule out deliberate deception. There are several ways of looking at promotion.

Pro-active promotional activities

Pro-active promotional activities are activities carried out with some forward-looking objective in mind. We might say that pro-active promotions are designed to bring about some state of affairs which the organisation thinks to be desirable.

Such promotional activities might be carried out in support of the organisation as a whole, or of a division or branch of the organisation. They might be carried out in support of a single product (as when a book publisher decides to promote one book from a list of 40 titles). They might be carried out in support of some marketing activity (such as launching a new product) or some financial activity or some corporate policy such as care for the environment.

Different industries have their own distinctive pro-active activities - the film industry invites reviewers to a private showing, the publishing industry organises author-signing sessions and a conference venue may run facility visits to woo potential conference organisers.

Reactive promotional activities

Reactive promotional activities are concerned with reacting, or responding, to situations which arise and which are not within the original plan. For instance, if a manufacturer were to suffer a factory fire, it would be necessary to reassure suppliers and customers that the company could cope with such a disaster and that it would be 'business as normal'.

Strategic promotional activities

Strategic promotional activities tend to be long term and are usually concerned with the overall direction that a company might take over a period of time. Entering a foreign market for the first time would be a strategic objective related to a market-development policy. Launching a new range of products would be a strategic objective related to a product-development policy. Holding on to market share would be a strategic objective related to a consolidation policy. All these policies would require a great deal of strategic promotional support. Strategic promotional activities are pro-active.

Tactical promotional activities

Tactical promotional activities tend to be short term and concerned with some very specific objective such as shifting a surplus of slow-moving stock. Although such an objective might have only a limited impact on a company's overall situation, the combined effect of a series of tactical promotions will work together to take the company closer to its strategic objective - assuming, of course, that the company has an integrated plan in which tactical objectives are put in place to support strategic ones. Tactical promotional activities may be either pro-active or reactive.

Promotional activities and internal and external publics

Promotional activities may be directed outwards at external publics or inwards at internal publics. It is often necessary to sell an externally directed strategy internally before it can be made to work and changes in company policy and procedure have to be internally promoted also.

Different types of promotional activity

Advertising

An advertisement is a message aimed at a specific audience paid for by an identifiable person or organisation (the advertiser) and appearing in any of the recognised media, such as magazines or newspapers. It is controlled by the advertiser. The fact that some newspapers give advertising space away does not undermine the general principle of advertising as a paid-for message. An economist would just say that the newspaper proprietors had set a zero price on their advertising space.

Press relations (media relations)

Press relations is an activity closely related to public relations with which it is often associated, as in the phrase 'public and press relations'. Press (or media) relations is a method of promotion designed to get messages into the editorial content of the media and it does so by developing professional relationships with journalists to get companies and their products mentioned favourably.

Some people dismiss this as 'free publicity' or 'free advertising', but that is to misunderstand the nature of both advertising and press relations.

Public relations

Public relations is wider than just press relations which it is often defined to include. Public relations is concerned with the systematic development and maintenance of mutual understanding between an organisation and its publics. Getting an organisation or its products mentioned on the radio, for example, is only part of this process.

Another way of looking at public relations is to say that it is concerned with developing and sustaining a positive image of the company and its products. Public relations is sometimes thought of as a supporting activity to marketing and advertising, but it is much more than this. Investors, suppliers, local councils, trade unions and government departments can all be target audiences for a public relations campaign.

Conferences and exhibitions

Conferences and exhibitions are discussed together because they have a great deal in common. Generically, they are referred to as meetings or events. A meeting is a formal situation where two (or more) groups of people, buyers and sellers for example, can come together to discuss matters of mutual interest and, sometimes, to carry out business transactions.

Sponsorship

Sponsorship is often called business sponsorship because most sponsorship deals today are funded by businesses. It is not a charity. Sponsorship involves a company funding an activity such as a football match or a pop concert in order to generate beneficial publicity for itself. The success, from the sponsor's point of view, of a sponsorship deal is the amount of good publicity it attracts. Sponsorship may be used to promote a corporate image or as part of a marketing campaign or a public relations campaign. Sponsorship support is usually, but not necessarily, in the form of money.

Direct marketing

Direct marketing is a generic term that covers a variety of ways of promoting a product or service directly to its final consumer or user without going through an intermediary. It involves the use of direct mail, telephone sales and calling on people at home. It is often associated with home shopping - shopping from home either by mail or telephone, for example.

Sales promotion

Sales promotion is another generic term that covers a very wide variety of practices which generally aim to motivate people in the closing stages of the purchase process and which are designed to bring about a successful sale. Sales promotions can operate at three levels: on the sales force, the wholesale and retail trade and, of course, the consumer.

Business-to-business promotions

All the promotional activities discussed above can be targeted at members of the consuming public. They may, however, also be targeted at other businesses so that we can talk of business-to-business advertising, business-to-business direct mail and so on.

Points to note

Under control

It should be observed that circumstances are rarely either totally controllable or totally uncontrollable. Something can go wrong with the best laid plans (a technicians' strike on television can ruin a carefully thought out advertising campaign). But situations apparently outside the company's control can still be influenced - by good public relations, for example.

Above and below the line

The terms above the line and below the line are often used and have their origins in the development of the advertising agencies. Originally, agencies made their living by buying media space on behalf of their clients. They made no profit on this from the client but instead earned a commission from the media. As the agencies expanded they took on more work on behalf of the client (sales promotion, for example) and on this they had to make a profit out of the client. The line in question was the one drawn across the page to distinguish the charges for media space (above the line) from the other charges (below the line) and the terms passed into common usage.

Summary

· Publicity, a term which can have the widest usage, also includes promotion which has a narrower meaning.

· Publicity includes all the statements made about a company or its products.

· Publicity may be controlled or non-controlled.

· Publicity uses any media.

· Publicity has different degrees of permanence.

· Publicity may be authorised or unauthorised; solicited or unsolicited; friendly, neutral or hostile; true or untrue.

· Promotional activities are those activities undertaken by (or authorised by) a company to get it posotove publicity. It may be proactive or reactive, strategic or tactical, inwardly or outwardly directed.

Promotion itself further subdivides into a range of promotional activities often divided into above-the-line (media advertising) and below-the-line activities.

text 35

Models of communication

Introduction

Communications are a part of the framework of policy and strategy. Some companies undertake a communications audit as part of their strategic analysis to see where their strengths and weaknesses lie in this area. A foreign language audit is a specialised form of communications audit which can be carried out by, say, a British firm thinking of entering the European market for the first time.

This book is about communication in a wide variety of forms and about the circumstances which influence the effectiveness of communication. We have already seen that communication about an organisation can originate from within the organisation or from some external source. Communications can be authorised by the organisation (this includes some externally originated messages) or unauthorised (even some internally originated messages can be unauthorised). Models of communication generally assume internally originated and authorised messages and that is what is assumed in this chapter. Unauthorised and externally originated messages will be built in to show the sort of effect that they can have.

In this chapter the word communication is virtually interchangeable with the word publicity but not entirely. All forms of publicity can be called communications, but not all forms of communication can be called publicity - instructions, requests for information, answers to such requests and formal reports are all communications which we would not want to call publicity. Models of communication, therefore, have a wider application than that which is under consideration here.

Communications objectives

Every communication must have a purpose in mind. Advertising objectives are often classified under the two headings of to inform and to persuade. These two headings cover all sorts of communication and it is difficult to think of any promotional activity that does not contain elements of each.

Inform

Target publics need to be informed of all manner of things: product specification, product availability, prices, after-sales service and many other items as well. When something new is being introduced to the market - a new product, a new service, a new branch of a retail chain - then the need to inform is very high. It is not only consumers who need to be informed and techniques such as public relations, direct mail and conferences can be used to inform employees, shareholders, local communities and government departments as well.

Persuade

Persuading is harder than informing. It may require the receiver of the message not only to understand what is being said but also to act on it in some way. Persuading may be at the level of simply changing somebody's perception of something (as in convincing worried employees that there are no redundancy plans in preparation) but usually we want people to do more than just change their minds. We want them to do something: buy a new product, carry on buying an old product, recommend the product to a friend and so on.

The relationship between informing and persuading is frequently summed up in what is sometimes called a hierarchical model. It is called hierarchical because it is believed that people begin at a lower-order level and move through progressively higher levels until they reach the highest-order level. In simple terms these would be:

· Cognitive. The lower-order level of simply knowing something.

· Affective. A higher-order level of letting what one knows influence what one actually thinks and believes.

· Behaviour. The highest-order level of translating what one thinks and believes into action.

In practice, it may not actually work out in such a neat hierarchical way. Some people do not progress beyond the cognitive stage. Others jump straight from the cognitive stage to the behaviour stage (the impulse factor). People at the behaviour stage may loop back to the affective stage to allow the experience of trying the product to modify what is understood and believed. They may even loop back to the cognitive stage because now they have tried the product they have new information or knowledge about it which they did not have before. Nevertheless, the hierarchical model for all its imperfections produces a message model of communications objectives based on the ideas of:

· Messages which merely inform.

· Messages which aim to change opinions and attitudes.

· Messages which encourage action.

Share of mind, front of mind and share of market

These different types of messages are sometimes associated with the concepts of share of mind and front of mind. We do seem to be limited as to what we can take in. Some things get into our minds and others don't. Whatever gets in has a 'share' of our minds and the more we think about things the greater the share they have. We are said to push things to the back of our minds when we do not wish to think about them, but this is the opposite of what the advertiser wants. The advertiser wants things at the front of our minds so 'share of mind' is often associated with the allied concept of 'front of mind'. The first two 'message models' listed above - messages that inform and messages that change opinions - are designed to get this share of mind/front of mind awareness. Because the third model is to do with action (actually buying something, for example),

Text 36

Public relations

Introduction

Public relations (PR) is often taken to include press relations. Here they are treated in two separate chapters. For a full understanding, chapters 14 and 15 should be read together.

Any organisation has a great number of publics with it will have a variety of relationships. Some of those publics will be of very great significance and able materially to affect the success or otherwise of the organisation. Some will be less significant. Some of the relationships will be of a steady and unchanging sort and others may be more volatile and even hostile. Every organisation needs to be aware of the nature and extent of its significant publics and of the quality and status of its relationships with them.

Public relations can be defined as the development and maintenance of positive relationships between an organisation and its publics. The word development places the responsibility on the shoulders of the organisation and the word maintenance identifies public relations as an on-going and continuous process.

Publics are sometimes referred to as audiences, but this implies an interest on the part of the publics, which they may not always have. They are sometimes reluctant audiences and the organisation may have to work hard to secure their interest. Publics are also sometimes identified with consumers and consumers are certainly an important public. Consumers are not, however, the only public.

Public relations is a communications activity that is unusual in being both a professional, highly skilled function on the one hand and something which everybody in the organisation can do on the other. In this chapter we are concerned with the profession of PR, but we should not ignore the other aspect.

Public relations as a non-specialist activity

Everyone in an organisation performs some sort of public relations function whether aware of it or not. To this comment can be added that every act of communication performs some sort of public relations function as well. Public relations as a separate specialist business function can succeed best if these two propositions are properly understood by everybody. In fact many external PR campaigns have to begin with changing the attitudes and behaviour of people inside the organisation and getting their support. The poor attitudes and behaviour of some people inside an organisation may actually be thought of as 'bad public relations' and be contributory causes to any PR problems the company has.

Every message sent out (whether oral or written) has a PR dimension regardless of its actual purpose - it may be well or badly written, well or badly designed, or both. Poorly designed sales literature, impolite receptionists, trucculent deliverymen, offensive advertisements - all create bad impressions. Professional PR cannot take the responsibility for all these failures, but neither can it be seen in isolation as though everything else that is done or said has no impact on the company's image and reputation. People not directly involved in PR might well be reminded that 'everything you do and everything you say tells somebody else something about what sort of organisation this is'. The formal recognition of this fact is seen when companies include public relations in the policy and decision-making process.

Public relations and corporate and business policy

Policy decisions always carry with them public relations implications. Some decisions can be anticipated to be unpopular and public relations can be of assistance in such situations in both pointing out the source and strength of possible resistance and in proposing ways of neutralising it. 'Public relations problems' are identified and 'public relations solutions' are proposed at the policy-making stage.

On the other hand, the policy decision may create 'public relations opportunities' of which the decision makers are unaware. In this case, public relations has the role of identifying such opportunities and proposing ways of exploiting them. The appointment of a new marketing director, the installation of new machinery, the launch of a new product' and the decision to relocate the company head office all offer public relations opportunities.

Where public relations expertise is involved at every stage of the decision-making process, PR problems and PR opportunities can be identified early and PR solutions and programmes put in place in a thoughtful and systematic way. This is what we call pro-active public relations: thinking ahead and defusing trouble or planning for maximum beneficial publicity.

Unfortunately, some companies have not always thought so positively about the public relations function and have tended to treat it more as a 'fire-fighting' function to be brought in to deal with problems if and when they arise or as a 'window dressing' operation designed to make the company look good regardless of the facts. This attitude to public relations is not acceptable.

It is not the role of public relations to make corporate or business policy decisions nor to sort out business problems and crises. These are management functions which must be carried out by those in charge. The role of public relations is to develop and protect the company's image during the policy- and decision-making stage and subsequently throughout the implementation period and beyond.

Managers may make decisions of which public relations practitioners do not approve, but beyond making their reservations clear and pointing out the public relations pitfalls they can only carry out their client's or employer's wishes unless, of course, they feel strongly enough to resign.

The variety of publics

As we have observed, consumers are an important public. But there are other marketing publics to be considered. Suppliers at the backward end of the value chain and wholesalers and retailers at the forward end are also important. The necessity of developing and maintaining good relationships with these is self-evident and relationship marketing which emphasises supplier and customer retention over the long term recognises this. It takes time and it costs money to develop a customer or a supplier and to lose them through poor relationship management is inexcusable.

Throwing a wider circle around the organisation, we can identify as publics the community at large, groups such as trade associations, trade unions, government departments and consumer associations and individuals such as members of Parliament, local government officials and the media.

The company's own employees form a significant internal public. Their co-operation and goodwill also needs to be developed and they also will, from time to time, need to be persuaded and reassured about company policy.

Hostile, friendly and neutral publics

A simple distinction is between friendly and hostile publics. A manufacturer should be able to regard such publics as consumers, suppliers and so on as friendly, although their goodwill should never be taken for granted. Any manufacturer, however, may also arouse, however innocently or unwittingly, the hostility of publics. Manufacturers of cosmetics have attracted the hostility of animal rights groups, tobacco companies have lived with hostility for decades now and some manufacturers of children's products, particularly electronic games and confectionery, have attracted the anger of some parents, educationalists and some of the medical profession.

Generally speaking, if a survey showed that 70 per cent of parents thought well of your company and its products you could say that, on the whole, parents were friendly. However, you would still have to think carefully about the other 30 per cent, particularly if later surveys showed the tide of opinion moving in their direction so that six months later only 65 per cent were favourable and 35 per cent were now against you.

The terms friendly and hostile are a bit extreme and are not the only possibilities. Publics may be neutral in their attitudes and indifferent to what the company is doing. They may even be ignorant of the company's existence altogether. This does not mean that they should be ignored - they may be indifferent to you (or ignorant of you), but that does not mean that you should not be interested in them.

When we talk about publics as being consumers, shareholders, suppliers, etc., it is easy to forget that no real person is ever just a consumer. Some of the company's consumers could also be among its suppliers, its shareholders and even its employees. It is not, therefore, possible to tell different stories to different publics and get away with it for very long. One of the advantages of a mission statement is that it focuses all sorts of messages in the same direction.

It is also important to recognise when a particular public is so adamantly hostile to you that you can never win it round and it is a waste of time trying. The point here is that you do not always need everybody on your side. In a contested take-over bid, all you need is a majority of the shares (not all of them) and in a general election a political party does not need all the seats (just more than the others).

| Friendlies | Hostiles | Neutrals | |

| Local councillors | Friendly councillors | Hostiles councillors | Neutrals councillors |

| Local residents | Friendly residents | Hostiles residents | Neutrals residents |

| Local businesses | Friendly businesses | Hostiles businesses | Neutrals businesses |

Fig. 14.1 Attitude matrix

Taking different types of publics and different attitudes a company could develop a matrix. A property developer, for example, could finish up with something like fig. 14.1.

Instead of treating all councillors as hostile or all businesses as friendly, the contractor could do some research and find out who is in each box. In PR terms, it might pay to treat the hostiles as a single public (regardless of whether they are residents, businesses or councillors) and see whether the grounds of their hostility are sufficiently alike to be dealt with by similar measures. For example, they might all have the same environmental objections to a new development - loss of civic facilities, increased traffic congestion, etc.

We can now see that publics:

• Can be made up of individuals (consumers or workers, for example) or of organisations (suppliers, retailers or agencies).

• Can be either very large (consumers may be numbered in tens or hundreds of thousands, even millions) or relatively very small (how many local councillors are there?).

• Can be internal or external to the organisation.

• Can be friendly, hostile or neutral.

• Can represent a wide variety of relationships with the company giving rise to different areas of public relations such as consumer PR, trade PR, supplier PR and internal PR.

We may also encounter product PR (to support an existing product or a new product launch), financial PR (aimed at shareholders) and PR which specialises in particular areas such as fashion PR.

Public relations crops up in different forms in non-business areas as well. Politicians and other public figures may have their own PR advisers. Local government utilises PR in communicating with residents and central government departments are among the biggest producers of press releases to publicise their decisions. Service organisations such as the police, ambulance and fire services also use public relations.

text 37

Sales promotion

Introduction

It is sometimes said of sales promotion that its purpose is to be there during the final stages of the purchase decision process, either carrying the customers over the line between purchase and non-purchase or affecting the characteristics of the purchase, such as its size or timing. In the latter case, sales promotions may affect people who would ha

– Конец работы –

Эта тема принадлежит разделу:

Аннотирование и реферирование английской научно-технической литературы

На сайте allrefs.net читайте: "Аннотирование и реферирование английской научно-технической литературы"

Если Вам нужно дополнительный материал на эту тему, или Вы не нашли то, что искали, рекомендуем воспользоваться поиском по нашей базе работ: The Nature and Role of Information

Что будем делать с полученным материалом:

Если этот материал оказался полезным ля Вас, Вы можете сохранить его на свою страничку в социальных сетях:

| Твитнуть |

Хотите получать на электронную почту самые свежие новости?

Новости и инфо для студентов