рефераты конспекты курсовые дипломные лекции шпоры

- Раздел Экономика

- /

- ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Реферат Курсовая Конспект

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ - раздел Экономика, ТЕМА 5 Неоинституциональные теории фирмы На Первичной Стадии Контрактация — Гибкий Институт. Стороны Трансакции Могут,...

На первичной стадии контрактация — гибкий институт. Стороны трансакции могут, по крайней мере в принципе, разработать все детали отношений соответственно своим конкретным нуждам. Однако во всех случаях, кроме простейших обменов, процесс изучения и оговаривания деталей трансакции может оказаться дорогостоящим. Вместе с тем многие основополагающие условия и положения, вероятно, являются общими для разных трансакций. Чтобы минимизировать сопряженное с издержками дублирование идентичных положений в отдельных контрактах, право предлагает ряд стандартных доктрин и средств, пригодных для рутинных процедур заключения контрактов. Так, и установленные судом наказания за нарушение контракта, и применение критериев обычного права в форс-мажорных ситуациях можно интерпретировать как субституты раз за разом повторяющихся в контрактных документах общих положений, регулирующих отдельные трансакции. В то же время суды признают разнородность трансакций и предоставляют сторонам широкую свободу по обоюдному согласию добавлять и изменять условия соглашения. Наличие совокупности стандартных доктрин, управляющих контрактным торговым обменом, в сочетании с возможностью «"выйти за рамки структур управления, предоставляемых государством, или оставить эти структуры в стороне", разработав частный порядок улаживания конфликтов» (Williamson, 1983, р. 520), делает конструирование контрактных отношений более экономным и гибким.

Однако нет оснований полагать, что распределение трансакций унимодально, т. е. логика, оправдывающая существование исходного множества общих правовых доктрин, может также служить основой для формирования альтернативных множеств норм и общепринятых правил (т. е. институтов), призванных управлять совершенно иными кластерами трансакций. Тем самым участникам трансакций предоставляется свобода маневра при разработке контрактов, что дает возможность изменять правила и средства с целью реализации любой желательной схемы. Например, модель отношения нанимателя и наемного работника можно скопировать с некоторого контракта, где детально оговорены определяемые законом обязанности и санкции хозяина и слуги, и тогда в случае конфликта эталоном будет этот контракт, а не прецедентное право. Но для этого независимо от намерений и целей потребуются обзор и повторение норм всего прецедентного права в каждом контракте, что, очевидно, весьма неэкономично. Напротив, опора на доктрины обычного права позволяет участникам трансакции выбрать комбинацию правовых "умолчаний" и "априорностей", допускающую наилучшее приближение к идеальному устройству дел в том смысле, что благодаря этим "умолчаниям" и "априорностям" в классе трансакций, к которому принадлежит планируемая сделка, можно по обоюдному согласию сторон осуществлять желательную для них дополнительную корректировку контракта.

Различия в правовых "умолчаниях", санкциях и процедурах, управляющих торговыми трансакциями и трансакциями найма соответственно, придают понятию фирмы уже не описательный, а конструктивный смысл. Теоретики, склонные к традиционным подходам, не сумели адекватно зафиксировать эти различия, и поэтому им было трудно идентифицировать специфику власти менеджмента или доступа к информации, обычно приписываемого интеграции, что привело ряд видных авторов к отрицанию роли внутренней организации в управлении трансакциями. В лучшем случае понятие фирмы приобретает конструктивный смысл только в контексте "активов (например, машин, товарных запасов), которые находятся в ее собственности" (Grossman and Hart, 1986, p. 692).

Однако с формальной точки зрения различие между ролью

фирмы как собственника и как структуры управления носит фиктивный характер. Право собственности само по себе является состоянием, поддерживаемым правовыми нормами и средствами защиты. Но изменение юридического статуса, очевидно, не приводит к физической трансформации актива. Меняются отношение действующих лиц экономики к этим активам, права и обязанности, которые определены и закреплены за ними правовой системой. Как писал Харолд Демсец, "проблема определения права собственности является в точности проблемой создания должным образом отрегулированных правовых барьеров для агрессивного проникновения" (Demsetz, 1982, р. 52), т. е. проблемой установления системы наказаний, призванной поощрять или пресекать определенные типы поведения. В этом отношении нет существенной разницы между правом менеджера руководить деятельностью наемного работника и правом собственника ограничивать использование актива или вообще его ликвидировать. На контроль над индивидами оказывают воздействие предусмотренные законом правила и наказания; то же самое справедливо и в ситуации контроля над физическим капиталом. И в том, и в другом случае стимулы, побуждающие агента подчиняться, зависят от санкций, которые может применить доверитель. Таким образом, хотя возможны различия в частностях (например санкции в случае неповиновения в сопоставлении с санкциями в случае воровства), право собственности, как и административная власть, в конечном итоге является вопросом управления.

В этой статье я исследовал вопрос о различиях между организацией внутри фирмы и внешним, или рыночным, обменом, опираясь на юридическую литературу по трансакциям найма и сопоставляя эти материалы с соответствующими доктринами коммерческого контрактного права. Хотя это исследование никоим образом нельзя считать исчерпывающем, оно показывает, что право действительно выявляет существенные различия в обязательствах, санкциях и процедурах, управляющих этими двумя видами обмена, и что эти различия, судя по всему, порождают значимые различия в стимулах действующих лиц при разном институциональном устройстве. Более того, характер этих различий подкрепляет традиционные воззрения на фирму в экономической науке. Результаты исследования подтверждают наличие преимуществ в смысле власти, маневренности и информации, которые обычно приписывают внутренней организации. Законы имеют тот эффект, что у наемного работника, заинтересованного в сохранении отношений найма, более сильные стимулы подчиняться требованиям нанимателя, чем у независимого подрядчика в аналогичной ситуации. Выявленные отличительные признаки и обязанности, похоже, нацелены на то, чтобы сделать наемного работника, насколько это возможно, "продолжением" нанимателя.

В то же время законы, поощряющие послушание наемного работника и наказывающие его за сокрытие актуальной информации, также, вероятно, лишают наемного работника инициативы, отбивают у него охоту вносить вклад в приобретение информации и вообще требуют от нанимателя большего надзора за наемным работником. Так, ответственность наемного работника за сокрытие информации хотя и снижает у него охоту утаивать информацию от нанимателя, но, возможно, еще в большей степени блокирует стимулы накапливать информацию, вследствие чего и возрастает необходимость надзора за наемным работником. Ответственность нанимателя за гражданские правонарушения его наемных работников также способствует усилению контроля над подчиненными. В силу нагрузки, которая в этих условиях ложится на ограниченную способность менеджеров эффективно управлять производством и обменом, интернализация последующих трансакций становится принципиально невыгодным делом, что, в конечном итоге, ставит предел размеру фирмы.

Как показал Рональд Коуз, принятие решения об интеграции зависит от сравнительных достоинств альтернативных вариантов выбора. В данной статье я ставил перед собой цель идентифицировать некоторые правовые нормы, влияющие на результат этих сравнений. За пределами статьи остались такие, несомненно, заслуживающие внимания вопросы, как, в первую очередь, эволюция этих норм, а также вопрос о том, способствуют ли эффективной организации такие специфические нормы, как доктрина отношений найма по усмотрению сторон. Остается открытым и вопрос о том, насколько важную роль играют формальные правовые доктрины в принятии организационных решений. Изменение правовых норм с течением времени и межведомственные различия при рассмотрении судами конфликтов по поводу найма должны в соответствии с этой аргументацией вносить изменения и в стимулы участников трансакций к интеграции торгового обмена, и в то, какую форму принимает интеграция. Благодаря этому увеличиваются возможности эмпирической проверки теории.

4. Williamson O.E. Comparative Economic Organization: The Analysis of Discrete Structural Alternatives[8]

Although microeconomic organization is formidably complex and has long resisted systematic analysis, that has been changing as new modes of analysis have become available, as recognition of the importance of institutions to economic performance has grown, and as the limits of earlier modes of analysis have become evident. Information economics, game theory, agency theory, and population ecology have all made significant advances.

This chapter approaches the study of economic organization from a comparative institutional point of view in which transaction-cost economizing is featured. Comparative economic organization never examines organization forms separately but always in relation to alternatives. Transaction-cost economics places the principal burden of analysis on comparisons of transaction costs—which, broadly, are the "costs of running the economic system" <…>.

1. Discrete Structural Analysis

The term discrete structural analysis was introduced into the study of comparative economic organization by Simon, who observed that

As economics expands beyond its central core of price theory, and its central concern with quantities of commodities and money, we observe in it ... [a] shift from a highly quantitative analysis, in which equilibration at the margin plays a central role, to a much more qualitative institutional analysis, in which discrete structural alternatives are compared.... <…> (1978, pp. 6-7).

But what exactly is discrete structural analysis? Is it employed only because ''there is at present no [satisfactory] way of characterizing organizations in terms of continuous variation over a spectrum" <…>? Or is there a deeper rationale?

Of the variety of factors that support discrete structural analysis, I focus here on the following: (1) firms are not merely extensions of markets but employ different means, (2) discrete contract law differences provide crucial support for and serve to define each generic form of governance, and (3) marginal analysis is typically concerned with second-order refinements to the neglect of first-order economizing.

1.1. Different Means

<…> I maintain that hierarchy is not merely a contractual act but is also a contractual instrument, a continuation of market relations by other means. The challenge to comparative contractual analysis is to discern and explicate the different means. As developed below, each viable form of governance—market, hybrid, and hierarchy—is defined by a syndrome of attributes that bear a supporting relation to one another. Many hypothetical forms of organization never arise, or quickly die out, because they combine inconsistent features.

1.2. Contract Law

<…> First, I advance the hypothesis that each generic form of governance—market, hybrid, and hierarchy—needs to be supported by a different form of contract law. Second, the form of contract law that supports hierarchy is that of forbearance.

1.2.1. Classical contract law

Classical contract law applies to the ideal transaction in law and economics in which the identity of the parties is irrelevant. "Thick" markets are ones in which individual buyers and sellers bear no dependency relation to each other. Instead, each party can go its own way at negligible cost to another. If contracts are renewed period by period, that is only because current suppliers are continuously meeting bids in the spot market. Such transactions are monetized in extreme degree; contract law is interpreted in a very legalistic way: more formal terms supersede less formal should disputes arise between formal and less formal features (e.g., written agreements versus oral amendments), and hard bargaining, to which the rules of contract law are strictly applied, characterizes these transactions. Classical contract law is congruent with and supports the autonomous market form of organization <…>.

1.2.2. Neoclassical contract law and excuse doctrine

Neoclassical contract law and excuse doctrine, which relieves parties from strict enforcement, apply to contracts in which the parties to the transaction maintain autonomy but are bilaterally dependent to a nontrivial degree. Identity plainly matters if premature termination or persistent maladaptation would place burdens on one or both parties. Perceptive parties reject classical contract law and move into a neoclassical contracting regime because this better facilitates continuity and promotes efficient adaptation.

As developed below, hybrid modes of contracting are supported by neoclassical contract law. The parties to such contracts maintain autonomy, but the contract is mediated by an elastic contracting mechanism. <…> Franchising is [an example] of preserving semi-autonomy, but added supports are needed <…>. More generally, long-term, incomplete contracts require special adaptive mechanisms to effect realignment and restore efficiency when beset by unanticipated disturbances.

<…> By contrast with a classical contract, this contract (1) contemplates unanticipated disturbances for which adaptation is needed, (2) provides a tolerance zone (of ± 10%) within which misalignments will be absorbed, (3) requires information disclosure and substantiation if adaptation is proposed, and (4) provides for arbitration in the event voluntary agreement fails.

The forum to which this neoclassical contract refers disputes is (initially at least) that of arbitration rather than the courts. <…>

Such adaptability notwithstanding, neoclassical contracts are not indefinitely elastic. As disturbances become highly consequential, neoclassical contracts experience real strain, because the autonomous ownership status of the parties continuously poses an incentive to defect. <…>

When, in effect, arbitration gives way to litigation, accommodation can no longer be presumed. Instead, the contract reverts to a much more legalistic regime—although, even here, neoclassical contract law averts truly punitive consequences by permitting appeal to exceptions that qualify under some form of excuse doctrine. The legal system's commitment to the keeping of promises under neoclassical contract law is modest <…>.

From an economic point of view, the tradeoff that needs to be faced in excusing contract performance is between stronger incentives and reduced opportunism. If the state realization in question was unforeseen and unforeseeable (different in degree and/or especially in kind from the range of normal business experience), if strict enforcement would have truly punitive consequences, and especially if the resulting "injustice" is supported by (lawful) opportunism, then excuse can be seen mainly as a way of mitigating opportunism, ideally without adverse impact on incentives. If, however, excuse is granted routinely whenever adversity occurs, then incentives to think through contracts, choose technologies judiciously, share risks efficiently, and avert adversity will be impaired. Excuse doctrine should therefore be used sparingly—which it evidently is <…>.

The relief afforded by excuse doctrine notwithstanding, neoclassical contracts deal with consequential disturbances only at great cost: arbitration is costly to administer and its adaptive range is limited. As consequential disturbances and, especially, as highly consequential disturbances become more frequent, the hybrid mode supported by arbitration and excuse doctrine incurs added costs and comes under added strain. Even more elastic and adaptive arrangements warrant consideration.

1.2.3. Forbearance

Internal organization, hierarchy, qualifies as a still more elastic and adaptive mode of organization. What type of contract law applies to internal organization'? How does this have a bearing on contract performance?

Describing the firm as a "nexus of contracts" <…> suggests that the firm is no different from the market in contractual respects. Alchian and Demsetz originally took the position that the relation between a shopper and his grocer and that between an employer and employee was identical in contractual respects. <…>

That it has been instructive to view the firm as a nexus of contracts is evident from the numerous insights that this literature has generated. But to regard the corporation only as a nexus of contracts misses much of what is truly distinctive about this mode of governance. As developed below, bilateral adaptation effected through fiat is a distinguishing feature of internal organization. <…> The implicit contract law of internal organization is that of forbearance. Thus, whereas courts routinely grant standing to firms should there be disputes over prices, the damages to be ascribed to delays, failures of quality, and the like, courts will refuse to hear disputes between one internal division and another over identical technical issues. Access to the courts being denied, the parties must resolve their differences internally. Accordingly, hierarchy is its own court of ultimate appeal.

<…> Whether a transaction is organized as make or buy—internal procurement or market procurement, respectively—thus matters greatly in dispute-resolution respects: the courts will hear disputes of the one kind and will refuse to be drawn into the resolution of disputes of the other. <…>

As compared with markets, internal incentives in hierarchies are fiat or low-powered, which is to say that changes in effort expended have little or no immediate effect on compensation. This is mainly because the high-powered incentives of markets are unavoidably compromised by internal organization <…>. Also, however, hierarchy uses flat incentives because these elicit greater cooperation and because unwanted side effects are checked by added internal controls <…>.

The underlying rationale for forbearance law is twofold: (1) parties to an internal dispute have deep knowledge—both about the circumstances surrounding a dispute as well as the efficiency properties of alternative solutions—that can be communicated to the court only at great cost, and (2) permitting the internal disputes to be appealed to the court would undermine the efficacy and integrity of hierarchy. <…>

2. Dimensionalizing Governance

What are the key attributes with respect to which governance structures differ? The discriminating alignment hypothesis to which transaction-cost economics owes much of its predictive content holds that transactions, which differ in their attributes, are aligned with governance structures, which differ in their costs and competencies, in a discriminating (mainly, transaction-cost-economizing) way. But whereas the dimensionalization of transactions received early and explicit attention, the dimensionalization of governance structures has been relatively slighted. What are the factors that are responsible for the aforementioned differential costs and competencies?

One of those key differences has been already indicated: market, hybrid, and hierarchy differ in contract law respects. Indeed, were it the case that the very same type of contract law were to be uniformly applied to all forms of governance, important distinctions between these three generic forms would be vitiated. But there is more to governance than contract law. Crucial differences in adaptability and in the use of incentive and control instruments are also germane.

2.1. Adaptation as the Central Economic Problem

<…> I submit that adaptability is the central problem of economic organization. <…> Changes in the demand or supply of a commodity are reflected in price changes, in response to which "individual participants . .. [are] able to lake the right action" <…>. I will refer to adaptations of this kind as adaptation (A), where (A) denotes autonomy. This is the neoclassical ideal in which consumers and producers respond independently to parametric price changes so as to maximize their utility and profits, respectively.

That would entirely suffice if all disturbances were of this kind. Some disturbances, however, require coordinated responses, lest the individual parts operate at cross-purposes or otherwise suboptimize. Failures of coordination may arise because autonomous parties read and react to signals differently, even though their purpose is to achieve a timely and compatible combined response. <…>

More generally, parties that bear a long-term bilateral dependency relation to one another must recognize that incomplete contracts require gapfilling and sometimes get out of alignment. Although it is always in the collective interest of autonomous parties to fill gaps, correct errors, and effect efficient realignments, it is also the case that the distribution of the resulting gains is indeterminate. Self-interested bargaining predictably obtains. Such bargaining is itself costly. The main costs, however, are that transactions are maladapted to the environment during the bargaining interval. <…>

Recourse to a different mechanism is suggested as the needs for coordinated investments and for uncontested (or less contested) coordinated realignments increase in frequency and consequentiality. Adaptations of these coordinated kinds will be referred to as adaptation (C), where (C) denotes cooperation. <…>

2.2. Instruments

Vertical and lateral integration are usefully thought of as organization forms of last resort, to be employed when all else fails. That is because markets are a "marvel" in adaptation (A) respects. Given a disturbance for which prices serve as sufficient statistics, individual buyers and suppliers can reposition autonomously. Appropriating, as they do, individual streams of net receipts, each party has a strong incentive to reduce costs and adapt efficiently. What I have referred to as high-powered incentives result when consequences are tightly linked to actions in this way <…>.

Matters get more complicated when bilateral dependency intrudes. As discussed above, bilateral dependency introduces an opportunity to realize gains through hierarchy. As compared with the market, the use of formal organization to orchestrate coordinated adaptation to unanticipated disturbances enjoys adaptive advantages as the condition of bilateral dependency progressively builds up. But these adaptation (C) gains come at a cost. Not only can related divisions within the firm make plausible claims that they are causally responsible for the gains (in indeterminate degree), but divisions that report losses can make plausible claims that others are culpable. <…> The upshot is that internal organization degrades incentive intensity, and added bureaucratic costs result <…>.

These three features—adaptability of type A, adaptability of type C, and differential incentive intensity—do not exhaust the important differences between market and hierarchy. Also important are the differential reliance on administrative controls and, as developed above, the different contract law regimes to which each is subject. Suffice it to observe here that (1) hierarchy is buttressed by the differential efficacy of administrative controls within firms, as compared with between firms, and (2) incentive intensity within firms is sometimes deliberately suppressed. Incentive intensity is not an objective but is merely an instrument. If added incentive intensity gets in the way of bilateral adaptability, then weaker incentive intensity supported by added administrative controls (monitoring and career rewards and penalties) can be optimal.

Markets and hierarchies are polar modes. As indicated at the outset, however, a major purpose of this chapter is to locate hybrid modes—various forms of long-term contracting, reciprocal trading, regulation, franchising, and the like—in relation to these polar modes. Plainly, the neoclassical contract law of hybrid governance differs from both the classical contract law of markets and the forbearance contract law of hierarchies, being more elastic than the former but more legalistic than the latter. The added question is How do hybrids compare with respect to adaptability (types A and C), incentive intensity, and administrative control?

The hybrid mode displays intermediate values in all four features. It preserves ownership autonomy, which elicits strong incentives and encourages adaptation to type A disturbances (those to which one party can respond efficiently without consulting the other). Because there is bilateral dependency, however, long-term contracts are supported by added contractual safeguards and administrative apparatus (information disclosure, dispute-settlement machinery). These facilitate adaptations of type С but come at the cost of incentive attenuation. <…>

One advantage of hierarchy over the hybrid with respect to bilateral adaptation is that internal contracts can be more incomplete. More importantly, adaptations to consequential disturbances are less costly within firms because (1) proposals to adapt require less documentation, (2) resolving internal disputes by fiat rather than arbitration saves resources and facilitates timely adaptation, (3) information that is deeply impacted can more easily be accessed and more accurately assessed, (4) internal dispute resolution enjoys the support of informal organization <…>, and (5) internal organization has access to additional incentive instruments—including especially career reward and joint profit sharing—that promote a team orientation. Furthermore, highly consequential disturbances that would occasion breakdown or costly litigation under the hybrid mode can be accommodated more easily. The advantages of hierarchy over hybrid in adaptation С respects are not, however, realized without cost. Weaker incentive intensity (greater bureaucratic costs) attend the move from hybrid to hierarchy, ceteris paribus.

Таблица 4.1 Distinguishing Attributes of Market, Hybrid, and Hierarchy Governance structures

| Governance structures | |||

| Attributes | Market | Hybrid | Hierarchy |

| Instruments | |||

| Incentive intensity | + + | + | |

| Administrative controls | + | + + | |

| Performance attributes | |||

| Adaptation (A) | + + | + | |

| Adaptation (C) | + | + + | |

| Contract law | + + | + | |

| + + = strong; + = semi-strong; 0 = weak |

Summarizing, the hybrid mode is characterized by semistrong incentives, an intermediate degree of administrative apparatus, displays semi-strong adaptations of both kinds, and works out of a semi-legalistic contract law regime. As compared with market and hierarchy, which are polar opposites, the hybrid mode is located between the two of these in all five attribute respects. Based on the foregoing, and denoting strong, semi-strong, and weak by + + , +, and 0, respectively, the instruments, adaptive attributes, and contract law features that distinguish markets, hybrids, and hierarchies are shown in Table 4.1.

3. Discriminating Alignment

<…> Asset specificity has reference to the degree to which an asset can be redeployed to alternative uses and by alternative users without sacrifice of productive value. <…> Asset specificity <…> creates bilateral dependency and poses added contracting hazards. It has played a central role in the conceptual and empirical work in transaction-cost economics.

The analysis here focuses entirely on transaction costs: neither the revenue consequences nor the production-cost savings that result from asset specialization are included. Although that simplifies the analysis, note that asset specificity increases the transaction costs of all forms of governance. Such added specificity is warranted only if these added governance costs are more than offset by production-cost savings and/or increased revenues. <…>

The ideal transaction in law and economics—whereby the identities of buyers and sellers is irrelevant—obtains when asset specificity is zero. Identity matters as investments in transaction-specific assets increase, since such specialized assets lose productive value when redeployed to best alternative uses and by best alternative users. <…> I begin with the situation in which classical market contracting works well: autonomous actors adapt effectively to exogenous disturbances. Internal organization is at a disadvantage for transactions of this kind, since hierarchy incurs added bureaucratic costs to which no added benefits can be ascribed. That, however, changes as bilateral dependency sets in. Disturbances for which coordinated responses are required become more numerous and consequential as investments in asset specificity deepen. The high-powered incentives of markets here impede adaptability <…>. When bilaterally dependent parties are unable to respond quickly and easily, because of disagreements and self-interested bargaining, maladaptation costs are incurred. Although the transfer of such transactions from market to hierarchy creates added bureaucratic costs, those costs may be more than offset by the bilateral adaptive gains that result.

Let M = M(k; q) and H = H(k; q) be reduced-form expressions that denotes market and hierarchy governance costs as a function of asset specificity (k) and a vector of shift parameters (q). <…> As described above, the hybrid mode is located between market and hierarchy with respect to incentives, adaptability, and bureaucratic costs. As compared with the market, the hybrid sacrifices incentives in favor of superior coordination among the parts. As compared with the hierarchy, the hybrid sacrifices cooperativeness in favor of greater incentive intensity. The distribution of branded product from retail outlets by market, hierarchy, and hybrid, where franchising is an example of this last, illustrates the argument.

<…>

4. Comparative Statics

<…> Assuming that the institutional environment is unchanging, transactions should be clustered under governance structures as indicated. <…> The purpose of this section is to consider how equilibrium distributions of transactions will change in response to disturbances in the institutional environment. That is a comparative static exercise. <…> The institutional environment is the set of fundamental political, social and legal ground rules that establishes the basis for production, exchange and distribution. Rules governing elections, property rights, and the right of contract are examples. <…>

4.1. Property Rights

What has come to be known as the economics of property rights holds that economic performance is largely determined by the way in which property rights are defined. <…> I focus on the degree to which property rights, once assigned, have good security features. Security hazards of two types are pertinent: expropriation by the government and expropriation by commerce (rivals, suppliers, customers).

4.1.1. Governing expropriation

<…> If property rights could be efficiently assigned once and for all, so that assignments, once made, would not subsequently be undone—especially strategically undone—governmental expropriation concerns would not arise. Firms and individuals would confidently invest in productive assets without concern that they would thereafter be deprived of their just deserts.

If, however, property rights are subject to occasional reassignment, and if compensation is not paid on each occasion (possibly because it is prohibitively costly), then strategic considerations enter the investment calculus. Wealth will be reallocated (disguised, deflected, consumed) rather than invested in potentially expropriable assets if expropriation is perceived to be a serious hazard. More generally, individuals or groups who either experience or observe expropriation and can reasonably anticipate that they will be similarly disadvantaged in the future have incentives to adapt. <…> Lack of credible commitment on the part of the government poses hazards for durable, immobile investments of all kinds—specialized and unspecialized alike—in the private sector. If durability and immobility are uncorrelated with asset specificity, then the transaction costs of all forms of private-sector governance increase together as expropriation hazards increase. In that event, the values of k1 and k2 might then change little or not at all. What can be said with assurance is that the government sector will have to bear a larger durable investment burden in a regime in which expropriation risks are perceived to be great. Also, private-sector durable investments will favor assets that can be smuggled or are otherwise mobile—such as general-purpose human assets (skilled machinists, physicians) that can be used productively if emigration is permitted to other countries.

4.1.2. Leakage

Not only may property rights be devalued by governments, but the value of specialized knowledge and information may be appropriated and/or dissipated by suppliers, buyers, and rivals. <…> Interpreted in terms of the comparative governance cost apparatus employed here, weaker appropriability (increased risk of leakage) increases the cost of hybrid contracting as compared with hierarchy. The market and hybrid curves in Figure 4.1 are both shifted up by increased leakage, so that k1, remains approximately unchanged and the main effects are concentrated at k2. The value of k2 thus shifts to the left as leakage hazards increase, so that the distribution of transactions favors greater reliance on hierarchy.

4.2. Contract Law

Improvements or not in a contract law regime can be judged by how the relevant governance-cost curve shifts. An improvement in excuse doctrine, for example, would shift the cost of hybrid governance down. The idea here is that excuse doctrine can be either too lax or too strict. If too strict, then parties will be reluctant to make specialized investments in support of one another because of the added risk of truly punitive outcomes should unanticipated events materialize and the opposite party insist that the letter of the contract be observed. If too lax, then incentives to think through contracts, choose technologies judiciously, share risks efficiently, and avert adversity will be impaired.

Whether a change in excuse doctrine is an improvement or not depends on the initial conditions and on how these trade-offs play out. Assuming that an improvement is introduced, the effect will be to lower the cost of hybrid contracting—especially at higher values of asset specificity, where a defection from the spirit of the contract is more consequential. The effect of such improvements would be to increase the use of hybrid contracting, especially as compared with hierarchy.

<…> A change in forbearance doctrine would be reflected in the governance cost of hierarchy. Thus, mistaken forbearance doctrine—for example, a willingness by the courts to litigate intrafirm technical disputes—would have the effect of shifting the costs of hierarchical governance up. This would disadvantage hierarchy in relation to hybrid modes of contracting (k2 would shift to the right).

4.3. Reputation Effects

One way of interpreting a network is as a nonhierarchical contracting relation in which reputation effects are quickly and accurately communicated. Parties to a transaction to which reputation effects apply can consult not only their own experience but can benefit from the experience of others to be sure the efficacy of reputation effects is easily overstated <…>, but comparative efficacy is all that concerns us here and changes in comparative efficacy can often be established.

Thus, assume that it is possible to identify a community of traders in which reputation effects work better (or worse). Improved reputation effects attenuate incentives to behave opportunistically in interfirm trade—since the immediate gains from opportunism in a regime where reputation counts must be traded off against future costs. The hazards of opportunism in interfirm trading are greatest for hybrid transactions—especially those in the neighborhood of k2. Since an improvement in interfirm reputation effects will reduce the cost of hybrid contracting, the value of k2 will shift to the right. Hybrid contracting will therefore increase, in relation to hierarchy, in regimes where interfirm reputation effects are more highly perfected, ceteris paribus. Reputation effects are pertinent within firms as well. If internal reputation effects improve, then managerial opportunism will be reduced and the costs of hierarchical governance will fail.

Ethnic communities that display solidarity often enjoy advantages of a hybrid contracting kind. Reputations spread quickly within such communities and added sanctions are available to the membership <…>. Nonethnic communities, to be viable, will resort to market or hierarchy (in a lower or higher k niche, respectively).

4.4. Uncertainty

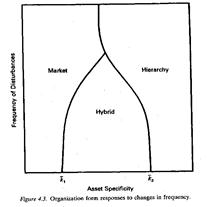

<…> Although the efficacy of all forms of governance may deteriorate in the face of more frequent disturbances, the hybrid mode is arguably the most susceptible. That is because hybrid adaptations cannot be made unilaterally (as with market governance) or by fiat (as with hierarchy) but require mutual consent. Consent, however, takes time. If a hybrid mode is negotiating an adjustment to one disturbance only to be hit by another, failures of adaptation predictably obtain <…>. An increase in market and hierarchy and a decrease in hybrid will thus be associated with an (above threshold) increase in the frequency of disturbances. As shown in Figure 4.3, the hybrid mode could well become nonviable when the frequency of disturbances reaches high levels.

<…> Although the efficacy of all forms of governance may deteriorate in the face of more frequent disturbances, the hybrid mode is arguably the most susceptible. That is because hybrid adaptations cannot be made unilaterally (as with market governance) or by fiat (as with hierarchy) but require mutual consent. Consent, however, takes time. If a hybrid mode is negotiating an adjustment to one disturbance only to be hit by another, failures of adaptation predictably obtain <…>. An increase in market and hierarchy and a decrease in hybrid will thus be associated with an (above threshold) increase in the frequency of disturbances. As shown in Figure 4.3, the hybrid mode could well become nonviable when the frequency of disturbances reaches high levels.

<…>

6. Conclusion

This chapter advances the transaction-cost economics research agenda in the following five respects: (1) the economic problem of society is described as that of adaptation, of which autonomous and coordinated kinds are distinguished; (2) each generic form of governance is shown to rest on a distinctive form of contract law, of which the contract law of forbearance, which applies to internal organization and supports fiat, is especially noteworthy; (3) the hybrid form of organization is not a loose amalgam of market and hierarchy but possesses its own disciplined rationale; (4) more generally, the logic of each generic form of governance—market, hybrid, and hierarchy—is revealed by the dimensionalization and explication of governance herein developed; and (5) the obviously related but hitherto disjunct stages of institutional economics—the institutional environment and the institutions of governance—are joined by interpreting the institutional environment as a locus of shift parameters, changes in which parameters induce shifts in the comparative costs of governance. <…>

5. Greenwood R., Empson, L. The Professional Partnership: Relic or Exemplary Form of Governance?[9]

Abstract

The creation of the public corporation in the 19th century drove out the partnership as the predominant form of organizational governance. Yet, within the professional services sector, partnerships have survived and prospered. Moreover, professional services firms that chose to abandon the partnership form tended to become private rather than public corporations. Drawing upon several theories, we compare the efficiency of the partnership relative to corporate forms of governance in the context of the professional services sector. We argue that the professional partnership minimizes agency costs associated with both the private and public corporation. We also argue <…> that partnerships have superior incentive systems for professionals in particular and knowledge workers more generally. However, drawing upon structural-contingency theory, we identify limiting conditions, which affect the relative efficiency of the partnership. We argue that the corporation, especially the private corporation, will be the preferred form of governance where the limiting conditions are prevalent. Nevertheless, we also argue that under specific conditions the partnership form of governance will persist and prosper because it remains unusually suited to the management of knowledge workers.

Introduction

<…> The professional partnership is deserving of study for several reasons. First, it is a form of governance that precedes the public corporation by several centuries <…> and exhibits high survival levels, especially in the field of business services. Second, the partnership is associated with the successful management of knowledge workers and, as such, has been praised as an exemplar for the 'new' economy <…>. Third, professional firms that use the partnership form of governance are significant entities, both in terms of their size and their role in the modern economy. <…>

The professional services industry consists of firms that provide advisory services to other businesses based upon the application of complex knowledge. Typically included within this industry are accounting and law firms, advertising agencies, architectural practices, management and engineering consulting firms <…> Three governance forms are extensively used: the professional partnership (including the limited-liability partnership), the private corporation, and the publicly traded corporation. The key legal distinctions between a partnership and a corporation are as follows: (1) a partnership does not have a legal identity in its own right; (2) it represents an agreement between two or more persons (the partners) carrying on a business in common with a view to profit; and (3) each partner is jointly and severally liable for the debts of the other partners. The partnership, in effect, contains multiple 'owner-managers' bound together by unlimited personal liability for the actions of their colleagues. A private corporation shares many of the characteristics of the partnership, but, crucially, does not impose unlimited personal liability upon its owners. The ownership of private corporations in the professional services sector, however, is similar to the partnership in that ownership is solely held by senior professionals active within the firm.

| Professional Sector | Firms (number) | Partnerships (%) | Private corporations (%) | Public corporations (%) |

| Law | ||||

| Accounting | ||||

| Management consulting | ||||

| Advertising | ||||

| Architecture |

Table 1 shows the frequency with which these three governance forms are used by the largest firms in several sectors of the global professional services industry. Law firms are always governed as partnerships and the partnership is also common among accountancy firms. Management consulting and architectural services firms are often partnerships, but more usually are private corporations. Large advertising agencies are (now) never partnerships and are usually private corporations. <…>

The above observations raise two interesting questions. First, why has the partnership form of organization survived and prospered in the delivery of professional services? <…> Second, why has the partnership form declined? These are important questions for organization theorists because they address how and why organizational forms evolve, survive, and decline.

In this article, we begin by using agency theory <…> to develop a series of hypotheses highlighting the efficiency of the professional partnership relative to corporate organizational forms as a governance mechanism for providing professional services. We argue that the professional partnership minimizes agency costs <…>. However, we also identify several factors which reduce the efficiency of the partnership. We suggest that these factors are increasingly significant among the professions, with the consequence that the corporate organizational form, both private and public, is becoming more efficient than the professional partnership and thus more widely adopted, especially by large firms. Nevertheless, we conclude that the partnership form will persist within the professional services sector because it is uniquely suited to the management of knowledge workers. <…>

The Efficiency of Organizational Forms

As Fama and Jensen (1983: 302) state, the form of organization that survives is that which 'delivers the output demanded by customers at the lowest price, while covering costs'. For these authors, the interesting question is, thus, which of two or more organizational forms meets customer needs most 'efficiently'. Following Fama and Jensen, we begin by drawing upon agency theory to help explain why the professional partnership form has survived in the professional services industry. We use agency theory for two reasons. First, it deals with the costs incurred by different governance structures, which is central to our interest. Second, it addresses the asymmetry of knowledge between client and supplier — a defining feature in the delivery of professional services <…>. However, we add to agency theory insights from property rights theory, tournament theory and structural-contingency theory in order to add a dynamic dimension.

Agency theory focuses upon the costs incurred in structuring, monitoring and enforcing contracts between principals and their agents. The theory rests upon two assumptions: that agents are motivated by self-interest and that the interests of owners (principals) and managers (agents) often diverge. <…> According to agency theory, principals monitor the agent's behaviour and use incentives that reward the agent for attaining the principal's goals. Using either mechanism incurs external agency costs resulting from the separation of ownership and control.

Costs incurred because of the separation of ownership and control are 'a special case' <…>, but not the only agency costs that an organization might experience. Internal agency costs occur where owners working within an organization delegate responsibility for management to a subgroup of their number <…>. This occurs in large partnerships in which a group of partners 'run' the firm on behalf of all partners. The interests of the managerial team may not coincide with the goals of the broader partnership; for example, senior partners often have shorter time horizons than their junior colleagues <…>. Thus, organizations may incur internal agency costs.

Following Podolny (1993), a third set of agency costs can be identified in the context of professional services firms, which we term 'status/reputation based' costs. These costs derive from the relationship between clients and suppliers of services <…>. Because services are intangible, clients find it difficult to evaluate their quality in advance of their consumption <…>. Even after a service has been delivered it is often extremely difficult for clients to assess quality <…>. Further, the capabilities of potential suppliers of services are usually shrouded in ambiguity. Exchanges between professionals and clients are thus a matter of high uncertainty for clients faced with the risks of moral hazard (the supplier may not put forth the agreed-upon effort) and adverse selection (the client incorrectly attributes competences to the supplier). Typically, agency theory asks how the client can minimize these risks. <…> Principals (in our case, clients) faced with high uncertainty seek social cues and 'signals' (such as a firm's reputation or status) from which they can infer competence and trustworthiness. A high reputation, or status, affects the efficiency of a firm by contributing three cost advantages <…>. Firms are able to charge premiums for their services because of the growing demand <…>. They incur lower marketing costs because clients actively seek the services of the firm. Similarly, hiring costs may be lower because recruits are attracted to the firm <…>. Third, reputation may create competitive barriers, in that clients will only select from the most reputable professional services firms (PSFs) to signal their own worth and rationality <…>. In other words, reputation enables the professional services firm to charge more for its services, to a growing list of clients, while at the same time reducing costs.

Organizational Forms and Professional Services

<…> Ownership is not necessarily internal to the partnership, but in practice external ownership is virtually unknown in the field of professional services, though sometimes retired partners retain their investment in the firm <…>. As such, there is no external agency problem equivalent to the shareholder-manager problem associated with the public corporation. Collectively, partners own and thus govern the partnership. Ownership and governance are also closely linked in the private corporation because ownership is usually contained within the firm. Because partnerships and private corporations share this characteristic, the latter often operate in much the same way as partnerships. Management consulting firms, such as McKinsey & Co. and Bain, even refer to themselves as 'partnerships' and their senior professionals (owners) as partners even though they are private corporations <…>.

A second critical characteristic distinguishes the partnership from the private corporation: the absence of 'asset partitioning' <…> and thus the risks of partnership. Asset partitioning defines which parties have claims over which assets and under which circumstances. Under the incorporation model, an owner's personal assets are partitioned from those of the corporate entity and thus protected. Legal claims against a corporation cannot extend to the personal assets of owners or employees. Partnerships, on the other hand, do not separate the assets of the partnership from the personal assets of partners (that is, partners have unlimited personal liability). Therefore, the partnership does not exist independently of the partners themselves, unlike the corporation, which is a separate legal entity. <…> Private corporations are able to protect personal assets, but the individual owner-manager is still significantly affected by the misconduct of colleagues because all of the firm's assets, which collectively 'belong' to the owner-manager, are exposed.

Partners are also liable for misconduct by fellow partners even if they themselves played no part in the misconduct or even had no knowledge of transgressions. Thus, not only are each partner's personal assets at stake, partners are also collectively accountable for the actions of colleagues. However, many jurisdictions now allow 'limited liability partnerships' (LLPs), which limit the personal liability of partners for the transgressions of fellow partners if they had neither knowledge of, nor involvement in, that work, while leaving the assets of the partnership fully exposed <…>.

The central point is that professional partnerships (including the LLP) are the most vulnerable, which, as we note below, significantly increases the risks to individual partners and has the effect of heightening deployment of 'mutual monitoring systems' <…>. The next most vulnerable are partners in the private corporation. We can thus regard partnerships and public corporations as end points of a continuum of risk, with the LLP and the private corporation at intermediate points.

Efficiency of the Partnership in the Delivery of Professional Services

Our starting proposition is that in the context of professional services, partnerships and the private corporation are more efficient than the public corporation because they incur no external agency costs. Ownership is typically contained within the firm: hence there is no external agency problem. However, professional partnerships and private corporations incur internal agency costs. As these entities reach a certain size, the responsibility for management typically is delegated to a small group of partners/owners. Often, those responsible for managing the firm are older partners/owners, whose interests may not coincide with the interests of younger professionals <…>. Senior partners, for example, may resist longer-term investments because the returns are not immediately received and do not advantage those approaching retirement <…>. Professional partnerships and private corporations thus have the challenge (and bear the costs) of aligning the actions of those managing the firm with the interests of all owners. This challenge is especially likely in large firms; the consequences of which are addressed later.

We suggest that internal agency costs incurred by professional partnerships and private corporations are unlikely to be as severe as the external agency costs incurred by the public corporation, for three reasons. First, partners are more knowledgeable about the business of the firm than are investors in public corporations, enabling them to monitor more efficiently the behavior of their agents <…>. Second, the proximity of partners to managers provides opportunities to exercise influence in a way not available to more dispersed shareholders. Third, managers are likely aware of the scrutiny of their colleagues. In short, professional partnerships and private corporations are more efficient than public corporations because their internal agency costs are lower than the external agency costs incurred by public corporations. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis I: Partnerships and private corporations are more efficient than public corporations in the delivery of professional services because they generate lower agency costs.

There are other reasons for expecting the partnership and the private corporation to be more successful than the public corporation in the management of professionals. They use more appropriate control processes, which provide incentives for sharing proprietary knowledge, and they deploy unique human resource practices that produce exceptional productivity.

Appropriate Control Processes

Professional service firms apply complex knowledge to non-routine problems. Morris and Empson (1998: 610) regard the knowledge aspect of the work as so important that they define a professional service firm as 'an organization that trades mainly on the knowledge of its human capital, i.e., its employees and the producer-owners, to develop and deliver intangible solutions to client problems'. Similarly, for Nachum (1999: 4), 'knowledge is... manipulated by highly educated employees and applied in order to provide a one-time solution to specific clients' problems'. Because of the customization of knowledge, formal hierarchies and bureaucratic control structures are unlikely to succeed <…>, for two reasons. The first <…> points to expectations of the 'professional' for autonomy and freedom from external constraint. This argument has particular application in a professional service firm because the firm is highly dependent upon its mobile workforce <…>. If professionals leave, tacit and relational knowledge is lost and clients may follow <…>. The second reason <…> points to the high costs involved in supervising non-routine behaviour. According to this perspective, it is more efficient to develop self-monitoring practices than to rely upon formal controls <…>.

These two arguments converge upon the same conclusion: the partnership and the private corporation are suitable vehicles for managing professionals because they use collegial rather than hierarchical controls, which are more typical of the public corporation with its emphasis upon targets and the close monitoring of results. As a consequence, partnerships and private corporations optimize the probability of job satisfaction, retention, and effort for professional workers.

Property rights theory <…> reinforces the utility of the partnership as an appropriate organizational form. It recognizes that where individuals possess knowledge which is critical to the firm, they should be encouraged to 'invest' their proprietary knowledge by sharing in the ownership of the firm and participating directly in decision-making. <…> The property rights approach, therefore, provides a justification for the persistence of the professional partnership, by emphasizing the importance of joint ownership of the key income-generating assets by the individuals who embody those assets.

In professional service firms, the knowledge of individuals represents the key income-generating asset, whether it is specialized technical knowledge about how to address clients' problems, or client-specific knowledge, derived from long experience of working with a particular industry, firm, or individual client <…>. Those who possess this valuable knowledge are potentially powerful within the firm. A key challenge for professional service firms is how to persuade these expert individuals to share their proprietary knowledge with their colleagues (and thus, potentially, undermine their unique power base) and to deploy it for the benefit of the organization as a whole <…>. Firms which seek to codify this knowledge face particular challenges in seeking to 'extract' this knowledge from individuals <…>. The partnership form of governance allows professionals to share directly in the benefits of their 'investment' of their proprietary knowledge by allowing an ownership stake in the firm — similar to a public corporation which offers substantial share options to employees. However, the additional characteristic which distinguishes the professional partnership from either the public or the private corporation is that, in addition to sharing in the ownership of the firm, partners also share in the management of the firm. Their ownership stake earns them the right to participate directly in key decisions. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 2: The partnership form of governance is better suited to the management of professionals than the private or public corporation as it (J) uses more efficient (collegial) control processes and {2) provides superior incentives for expert individuals to share proprietary knowledge.

Human Resource Practices

Professional partnerships, as they developed through the 20th century, incorporated unique human resource practices that go beyond the substitution of self-monitoring for hierarchical controls. <…> Two practices are especially interesting: an apprenticeship system, in which recently licensed professionals learn under the tutelage of seasoned partners and gain tacit knowledge; and an up-or-out approach to promotion, in which professionals considered unsuitable for admission to partnership exit the firm <…>. These practices motivate professionals, lured by the riches of partnership, to work excessively hard <…>. That is, the goals of owners and professionals are aligned. The lure of partnership as a motivator is so important that some firms <…> have reverted back to the partnership form in order to broaden opportunities for employees to share ownership (and the profits) of the firm. <…> Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 3: Partnerships and private corporations that use tournament career practices are more efficient than public corporations in the production of professional services because they offer superior career incentives to professionals, which result in higher effort and productivity.

Thus far we have suggested that the professional partnership is superior to the public corporation in the management of professionals because of its lower external and internal agency costs, its effective control processes, and the motivational advantage provided by use of the up-or-out tournament career system. There may be a further advantage, based on the third agency issue raised earlier, namely, the asymmetry of knowledge between purchasers of services <…> and professional suppliers. <…> We suggest that professional partnerships benefit from their status as partnerships and gain the advantages of lower operating costs. These lower costs, according to Podolny, accrue because clients use reputation as a signal of quality: we wish to argue that professional partnerships enjoy higher reputations than corporations.

It is difficult to be sure of when and why the professional partnership was first used, but case histories of law and accounting firms attest to its early and popular usage because of its association with high standards of client service <…>. That is, the partnership format traditionally acted as a signal of quality. <…>

<…> In other words, the professional partnership is supposed to make the client the primary beneficiary, whereas the corporation openly privileges the shareholder. The corporate form legitimately attends to the interests of the shareholder with the result that commercial success supplants or qualifies service as the primary motive.

In fact, it is not at all clear that professional partnerships protect clients from opportunistic behaviour. The mere absence of shareholders says nothing about how the tension between commercial interests and the ethic of service is resolved <…>. It could be argued that clients <…> might be more vulnerable to opportunistic behaviour under a partnership (or private corporation) because benefits from such behaviour would flow directly to the partner (or, in the case of the private corporation, to the owner-managers) not to a third agent. In practice, opportunistic behaviour likely does occur. <…> Nevertheless, there is an interesting literature that argues that to be the case. Sharma (1997), for example, states that professionals are constrained from engaging in opportunistic behaviour under specific conditions, which, we propose, are found in professional partnerships and private corporations, but less so in public corporations. First, in partnerships and the private corporation, professionals dominate the decision-making hierarchy. Some professional associatio

– Конец работы –

Эта тема принадлежит разделу:

ТЕМА 5 Неоинституциональные теории фирмы

На сайте allrefs.net читайте: "ТЕМА 5 Неоинституциональные теории фирмы "

Если Вам нужно дополнительный материал на эту тему, или Вы не нашли то, что искали, рекомендуем воспользоваться поиском по нашей базе работ: ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Что будем делать с полученным материалом:

Если этот материал оказался полезным ля Вас, Вы можете сохранить его на свою страничку в социальных сетях:

| Твитнуть |

Хотите получать на электронную почту самые свежие новости?

Новости и инфо для студентов