REVEALING SECRETS OF NUCLEAR FISSION

Enrico Fermi and his colleagues missed a reaction in the uranium which would later be determined to be the first example of nuclear fission. The task, therefore, fell tî scientist Otto Hahn, who was fast closing in on the secrets of fission. Hahn had studied in his native Germany, and in Britain and Canada, where he had worked with Rutherford and made several key breakthroughs, including the discovery of radiothorium and radioactinium. Returning to Germany in 1906, the next year Hahn began a decades-long

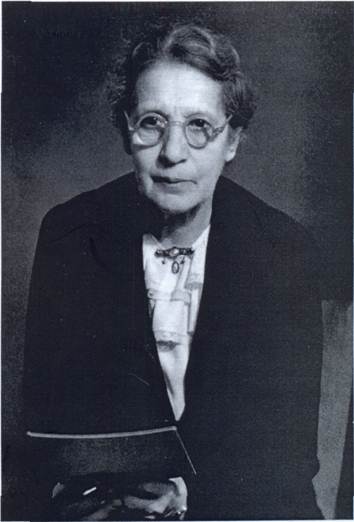

| Lise Meitner(1878- 1968) was a key figure in the discovery of fission. Born in Austria, Meitner graduated from the University of Vienna with a doctorate in 1906, and moved to Berlin to work with Max Planck and (Otto Hahn at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry. Closely collaborating with Hahn, Meitner helped make a number of breakthroughs in the study of radioactivity.Fleeing Hitler’s Germany in 1938 because of the Jewish ancestry, Meitner worked in Sweden, and continued to collaborate with Hahn from abroad, between them designing the experiments that proved that it was possible to split the atom to release energy. (Bridgeman Art Library) |

|

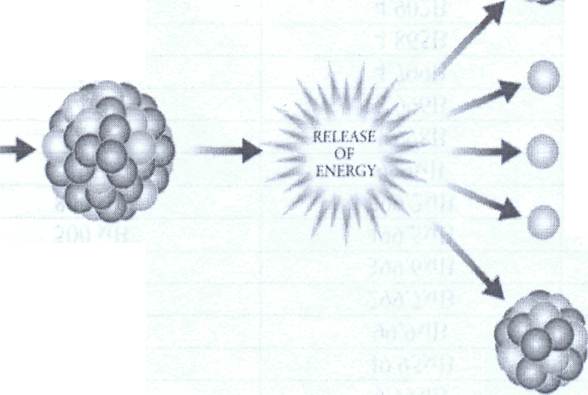

Nuclear fission occurs when an atom “splits”. A uranium 235 atom struck by a neutron fissions into two new atoms, free neutrons and binding energy. For a chain reaction (and a nuclear explosion) to occur, the free neutrons must strike other atoms and split them.

collaboration with Austrian scientist Lise Meitner. Working at the University of Berlin, the two jointly investigated radioactive transformation, and the qualities of beta rays. With Hahn’s student and assistant Fritz Strassman, the two followed Fermi’s work closely and inspired by his results, they began their own series of experiments, bombarding uranium with neutrons. Their great breakthrough came in 1938.

That year was a difficult one. Hitler’s rise to power in Germany had already seen the forced removal of Jewish scientists and academics, including Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, who had fled abroad. Lise Meitner, with Jewish ancestry, also Jell under the Nazi definition of a Jew, but .is an Austrian national had avoided dismissal and worse. The Anschluss of 1938, with Austria becoming part of the Third Reich, changed her position. One step ahead of the Gestapo, and with the help of Hahn and other friends, Meitner slipped across the Dutch border and made her way to neutral Sweden in July.

With Meitner collaborating via correspondence, the team kept up their work. In December, after bombarding uranium with neutrons, Hahn and Strassman found traces of barium and other elements. The “radium-barium-mesothorium-fractionation” experiment, as it came to be known, demonstrated to Hahn that: the bombardment had Split (Hahn used the term “burst”) the nucleus of the uranium nucleus into the atomic nuclei of the various other elements.

Hahn and Strassman reported their results in late December in an article in a weekly scientific publication, and sent the results to Meitner for analysis. Working with her nephew, refugee scientist Robert Frisch, who was then visiting her, Meitner agreed that the results showed that the nuclei had been split into their lighter elements, releasing neutrons and photons. Frisch coined a new phrase, “fission”, to describe the phenomenon. Hahn and Strassman published an article describing the tests, and Meitner and Frisch separately published on the physics to avoid Nazi censorship. In February 1939, Hahn and Strassman published another article, predicted, as Frisch had pointed out in the analysis he and Meitner had undertaken, that additional neutrons existed and had been released in the experiment. Reading that, Frederic Joliot-Curie and his team were able to replicate Hahn and Strassman’s results - an important scientific proof that the results from Berlin were not a one off, or in error.

Word quickly spread throughout the international community. Physicists in Europe and in the United States were quick to grasp the implications of fission - a number of them, like Szilard, had read The World Set Free. Now thanks to Hahn, Strassman, Meitner, and Frisch’s work, the possibility of generating a nuclear chain reaction a self-sustaining and self-sustaining and amplifying release of neutrons - was no longer just science fiction, Siitard, who had secretly patented the concept, knew it. Neils Bohr, looking at the various isotopes of uranium, specifically uranium-235 and ranium-238 (U-235 and U-238), realized how both could be fissioned. Ernest Lawrence’s laboratory partner at the Universityof California, Berkeley, J. Robert Oppenheimer, came to a similar conclusion, realizing that the rapid release of excess neutrons, if a chain reaction occurred, meant thatan atomic bomb could be built. That was also very clear to Albert Einstein. Like many of the refugee scientists who had fled Hitler; Einstein also realized, with chilling certainty, that if the Nazis grasped the potential and followed through on Hahn and Strassman’s breakthrough, the world was at risk. With that foremostin his mind, and urged on by colleagues, Einstein sat down to write a private letter to the President of the United States.

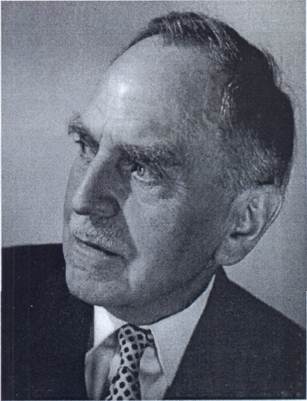

| Frankfurt-born Otto Hahn (1879-1968) was a brilliant chemist who joined Berlin's Kaiser Wilhelm institute for Chemistry. Closely collaborating with Austrian physicist Lise Meitner, Hahn eventually hearted the Institute and was its director until Germany's surrender at the end of World War II, when he was taken into custody by the Allies and interrogated along with other German atomic scientists. Hahn, despite his role in discovering the fission of uranium with Meitner and Fritz Statesman, bad not supported atomic weapons development, and was after the war a prominent advocate against nuclear weapons (Bridgeman Art Library) |

|