HENRI BECQUEREL AND THE CURIES’ DISCOVERIES

X-rays were only the first, surprise of the 1890s. New rays were soon detected which proved to be even more profoundly alien to known science.

The French physicist Antoine Henri Becquerel thought that X-rays might be pr___ fluorescence. So, one by one, he took fluorescent compounds and put them on a photographic plate «rapped in black paper. He left this outside, hoping that sunlight would make the compound fluoresce and produce X-rays, which would pas-; through the paper and darken the plate. In February 1896 came a seeming success: uranium potassium sulphate.

But then, one sunless day; he put a packet away in a drawer. Weeks later when he developed the plate, it ton had darkened. Becquerel had been wrong about fluoresce. Instead, uranium was spontaneously giving off penetrating rays. Other elements did this too.

Inspired by Becquerel’s work, Marie Curie pursued the analysis of rays emitted by pitchblende, the ore from which uranium is extracted, as well as various uranium compounds between 1897 and 1898. Rather than use photographic plates, she used an electrometer (a device invented by her husband Pierre and his brother Jacques to detect extremely low electrical currents) to measure the electrical discharge of the rays in air. Using this delicate instrument in difficult conditions, Curie measured very faint currents in the air after bombarding it with uranium rays.

She later explained: It was at the close of the year 1897 that I began to study the compounds of uranium, the properties of which had greatly attracted my interest. Here was a substance emitting spontaneously and continuously radiations similar to Roentgen rays, whereas ordinarily Roentgen rays can be produced only in a vacuum-tube with the expenditure of energy. By what process can uranium furnish the same rays without expenditure of energy and without undergoing apparent modification? Is uranium the only body whose compounds emit similar rays? Such were the questions I asked myself...

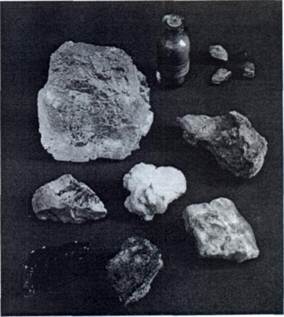

| In the collections of the Institut de Radium in Paris are minerals and rocks used by Marie Curie in her radiation experiments. Bombarding minerals with uranium rays, Curie discovered that the samples released energy in the form of rays. Deducing that the energy came from atoms, by 1989 Madame Curie had named the rays “radioactivity” based on the Latin word for ray. Among those shown here are carmolite, radium, lepidolite, lurite, toberinite, and rock salt. (Bridgeman Art Library) |

In this fashion, Marie Curie determined that the rays were constant, and that minerals with a higher proportion of uranium emitted the strongest rays. Were the rays a product of the atomic structure of uranium? Curie believed so, hypothesizing that they were evidence of the atomic structure of uranium, and that the energy released in the form of the rays came from atoms. While not sure that the energy came from the atoms or from cosmic rays caught by atoms and reflected back (which was not the case), Curie’s work suggested that atoms were not solid, elementary particles, particularly if they shed something in the form of rays.

Working with other mineralsamples, Curie found that thorium, like uranium, emitted rays. By 1898, Curie felt strongly enough that the rays were an atomic property, and she named it “radioactivity”, based on the Latin word for ray. Joined now by her husband Pierre, who set aside his own research to assist her, Marie Curie made another breakthrough:

I found, as I expected, that the minerals of uranium and thorium are radioactive; but to my great astonishment, I discovered that some are much more active than the oxides of uranium and of thorium, which they contain. Thus a specimen of pitchblende (oxide of uranium ore) was found to be four times more active than oxide of uranium itself This observation astonished me greatly. What explanation could there be for it?...The answer came to me immediately: The ore must contain a substance more radioactive than uranium and thorium, and this substance must necessarily be a chemical element as yet unknown...

Working to chemically separate the ore into separate elements, the Curies isolated two hitherto unknown and highly radioactive elements in 1898, which Marie Curie named polonium and radium. Isolating a sample of sufficientsize - one tenth of a gram of pure radium chloride - took the Curies more than three years of backbreaking and expensive work. Eight tons of pitchblende, when processed, ultimately yieldeda gram of radium.